Love Your Problems - Examples from Munich and Joburg

Mindful Design #10

Welcome to the Mindful Design Newsletter #10 where we look at how the trickiest problems can become standout features of a city, a home, even a room.

Since my rant about Pinterest I wanted to make sure that the examples shown here are rooted in real-life experiences and actual projects.

River revival

Let’s start with the ‘rewilding’ of a river that helped Munich in Germany become one of the most liveable cities in the world.

The beginning of our walk - sketch: Thorsten Deckler

Earlier this year, I found myself walking along the banks of the Isar River in Munich. My partner and I encountered swans, school children, runners, cyclists, and nudists all enjoying a beautiful spring day out. Our walk took us past beaches where we collected curious stones, down forest paths, over bridges, and through tunnels. The occasional glimpses of housing blocks, industrial structures, and graffiti reminded us that we were still in a city, which somehow made the whole experience even more thrilling. Also, swans are freaking huge!

Isar River after rehabilitation - image: Panorama – Solutions for a Healthy Planet

In the past, the Isar was used to transport goods, dispose of waste, and generate electricity. It was significantly re-engineered and channeled for these purposes. But pollution and flooding became so bad that an extensive rehabilitation project was launched in the 1990s. Now the Isar is clean and less flood-prone, but more significantly, it forms an amazing habitat for both wildlife and humans that stretches for miles through the middle of Munich and beyond.

From industry to culture

Still in Munich, our friend Susanne gave us a tour of the new creative and cultural hubs that have sprung up over the past 10 years on land that was previously occupied by industry.

The Bahnwaerter Thiel complex - image: Munchen.de

One of the hubs we visited was Bahnwaerter Thiel, a complex of artists' studios, clubs, and restaurants comprising containers and repurposed rail carts.

Alte Utting - image: Thorsten Deckler

The barge being installed - image: Bored in Munich

The other was Alte Utting, a decommissioned tourist barge fitted out as a cultural event and leisure space, perched on railway tracks above a busy road.

Visiting these projects felt like entering another dimension, one in which art, graffiti, music, and counterculture form an exhilarating contrast to the staid historic spaces of Munich, where Gemütlichkeit* is preserved – minus the creepy history.

*Gemütlichkeit - is a German term to convey a state or feeling of warmth, friendliness, and good cheer.

Feldherrenhalle - sketch: Thorsten Deckler

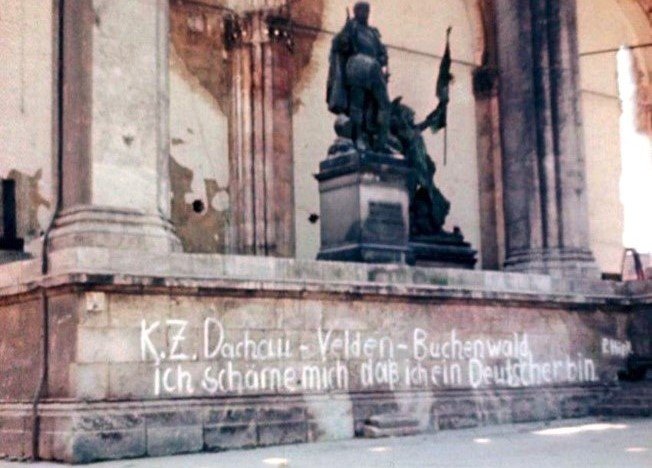

Graffiti from 1945 listing concentration camps and the words "I am ashamed to be German" - image: samilhistory.com

A case in point is the Feldherrenhalle, an elegant loggia overlooking a bustling square. It was here that the Nazis attempted their first coup and, once in power, regularly held their rallies. In the 1990’s the Bavarian government had to pass legislation to refrain contemporary right-wing groups for holding further public events here. Should the graffiti painted on the monument at the end of World War II have been preserved? Perhaps the energy of Munich’s creative quarters is a far more effective way to nurture a tolerant, open-minded society?

The repurposing of Munich's industrial sites and the rewilding of the Isar don’t just solve the problem of vacant land and a flooding river. Both initiatives transcend the ‘problem to be solved’ by creating entirely new opportunities to live, work, party, identify, and rescript the city.

Sad you don’t live in Munich?

Me too, so here’s an example closer to home to cheer us up.

Matchbox

In parts of South Africa, a new kind of city is rising from the old. People living in townships created during Apartheid are, out of necessity, transforming their matchbox homes, adding rental rooms and businesses. The collective result is a large-scale DIY make-over of the dreary dormitory towns built to control black workers. Watch me and fellow architect Tebogo Ramatlo as we explore Diepkloof, Soweto. Soon to be seen on Netflix (maybe) - lol!

Our debut as TV presenters - image: Heather Mason

So, what’s to learn from Munich and Soweto?

Recognising a problem as an opportunity for holistic change rather than an isolated problem to fix delivers solutions that are life-affirming, and sustainable with a much lower risk of creating new problems.

Ok, so you’re not re-wilding a river or building a city.

Here are two simpler examples.

River house

Our clients dreamed of a holiday house, outside the city, ideally near a river. After finding the perfect riverfront property, they imagined a long house in which all rooms face the river, the view, and the sun. But once they learned about the flood line, they realised that the land was largely unbuildable. After consulting with the water authorities and exploring several options, they settled on raising part of the house on stilts with a carport below. The striking form is a direct result of creatively responding to the flood line problem. Read more here.

River House - image: David Southwood

The dining room and upstairs bedroom converted into an atrium with overlooking ‘balconies’ and a new skylight - sketch: Thorsten Deckler

Letting light in

S and F are excited about renovating their new home and one of the most important things for them is the feeling of connection as a family. They hate the gloomy dining room and bedroom above it and came up with the idea of an atrium to let light in and create the connection they so dearly desire. With balconies for books and hobbies, the atrium breathes life and light into the worst part of their house. Without the problem dining room they may not have arrived at this solution.

All the examples mentioned here don't just solve problems, they transcend them by meeting primary emotional needs – like connecting to nature, expressing one’s individuality, living in community, escaping the city, and connecting to loved ones.

As humans (and architects!) we’re tempted to rush into problem-solving mode when faced with a challenge. We get caught up in the nitty gritty and run the risk of losing sight of the bigger picture and how we want to feel once your project is complete.

Do you know how you want to feel in your new space?

Here are some resources to help you get started:

Why do you want to build?

Read more about why asking ‘why’ is one of the most important things you can do BEFORE you rush into design.

Project Planning Pack: A workbook to help you figure out what you want and what it will cost.

Expert Call: A free 30-minute call to help you gain clarity on your project an the best step forward.

Needs and Option Review: A video on how to mitigate the risk of cost overruns and not getting what you want.

Found this useful? Let me know and please share with someone who you think needs this.

Why? Because we can build a more beautiful world.

Thorsten.

Thorsten Deckler is an architect based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He helps people create spaces that prioritize human well-being by employing the Mindful Design Approach. You can see his practice’s work at 2610southarchitects.com and more of his sketches on Instagram @thethinking_hand.